It may be useful to begin to familiarize yourself with the perspective drawing.

Choosing a plane of symmetry of the polyhedron (if any) as frontal plane is obviously an interesting option. In fact, this is what one does intuitively in the classical drawing of a parallel perspective of a cube.

The polyhedra the most easy to draw are obviously those stemmed from truncations or cuttings of the cube; the regular octahedron allows also to achieve elementary drawings. Here are a few examples:

starting from the cube

A truncation through the midpoints of three convergent edges leads to the cuboctahedron; the centers of three convergent faces define a face of the regular octahedron; for the truncated cube we have to use the regular octagon; concerning the small rhombicuboctahedron, its 48 edges are the sides of six regular octagons, two by two "parallel or orthogonal" (the vertices of the solid are the 24 vertices of six squares; the central symmetries about the centers of the cube's faces allow to place this points easily).

Using the centers of the cube's faces, we get the Kepler star (anticube).

By adding on each face of the cube (edge e) a pyramid with square base and a hight e/2 we get the rhombic dodecahedron; likewise by adding on each face a pentahedron-shaped "roof" (height h=e/2φ and length of the top edge l=2×h=e/φ where φ denotes the golden ratio, that means around e×0.3 and e×0.6) we get the regular dodecahedron (see the animations).

starting from the regular octahedron

A truncation passing through the midpoints of four convergent edges leads to the cuboctahedron; by passing through the centers of four convergent faces we get again the cube; to get the truncated octahedron (lord Kelvin's polyhedron) we have to go through the thirds of four convergent edges.

| The drawings of regular prisms (resp. of regular pyramids) remain also quite elementary: we draw a base in a vanishing plane, then we deduce easily the other base (resp. the summit). Only the regular prisms of even order have a center of symmetry. |  |

| For the regular antiprisms we have in addition to construct the high (distance between the basis) using a right-angled triangle whose hypotenuse is an altitude of a triangular face, but the existence of a center of symmetry (for all orders) makes the construction of the second base easier. |  |

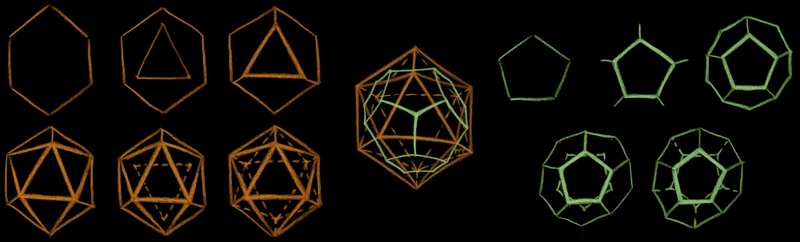

| OWe draw the regular icosahedron using three golden rectangles with same center and two by two orthogonal.

We may now deduce the icosidodecahedron whose vertices are the midpoints of its thirty edges; by using the centers of its twenty faces we get its dual, the regular dodecahedron. A game of patience... The drawing of the regular dodecahedron is much more easier by starting from the cube. |

|

Although is means to renounce the pleasure to handle the ruler and the compasses, you may achieve theses constructions using a geometric drawing software.

With a little training one may also draw freehand (reference: La tante et les polyèdres by Patrick Popescu-Pampu - in French)

After having drawn them, you may also build yourself some nice polyhedra, using cardboard, soldered copper wire, wood...

| references: |

• Dessiner l'espace by Michel Rousselet (published by Archimède - 1995), in French

• Shapes, Space and Symmetry by Alan Holden (Columbia University Press - New-York - 1971) • Polyhedron Models and Dual Models by M.J.Wenniger (Cambridge University Press, 1971-96 & 1983) • Polyhedra by Peter R.Cromwell (Cambridge University Press, 1996) |

home page

|

convex polyhedra - non convex polyhedra - interesting polyhedra - related subjects | August 1999 updated 01-09-2014 |